How Scoliosis Affects Movement, Flexibility, and Aging

The response to Scoliosis Syndrome confirmed something important: once scoliosis is understood as more than a curve, the questions shift.

They move away from “What exercise should I do?” and toward “What does this mean for my body long-term?”

That shift matters.

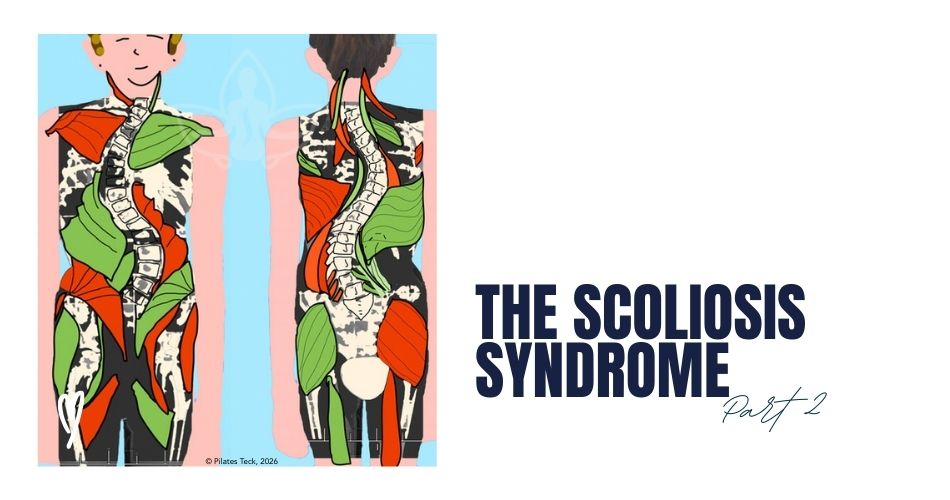

Scoliosis is not a localized spinal issue. It is a whole-body adaptation, muscles, fascia, bones, and the nervous system reorganizing around the shape of the spine. Movement, flexibility, and long-term health must be considered through that lens.

Movement Beyond “Tight and Weak”

Traditional scoliosis exercise models often rely on identifying tight muscles on one side and weak muscles on the other. While this framework captures part of the picture, it misses the deeper story of how the body adapts.

The reality is more nuanced.

Some tissues are lengthened—not because they’re flexible, but because they’ve been under constant tension for years. Others are shortened and compressed by the structural pattern of the curve. Strength and weakness don’t exist in isolation; they exist in relationship to structure.

This is why scoliosis exercise must be three-dimensional.

Effective movement emphasizes:

- Elongation – creating length through the spine

- Gentle de-rotation – addressing the rotational component of the curve

- Asymmetrical strengthening – informed by your individual curve pattern

In Scolio-Pilates®, breath and length come first, creating the conditions for muscles to work more evenly and with less strain. Generic workouts may improve fitness, but they rarely address alignment. And without alignment, you’re building strength on top of imbalance.

Scolio-Pilates® On Demand: Your Home Practice Library

Flexibility Requires Precision

Flexibility in scoliosis is one of the most misunderstood concepts.

More stretching is not always better.

Some areas of your body are already overstretched and depend on residual tension for stability. Stretching these regions further can reduce support and increase imbalance. Think of the concave side of a curve—tissues there are often already lengthened beyond their ideal range.

Other areas—particularly on the convex side—are shortened, compressed, and genuinely benefit from targeted lengthening.

The distinction is essential.

Flexibility work must be specific to the curve, not generalized. The goal isn’t symmetrical range of motion; it’s functional balance. You’re not trying to make both sides the same—you’re trying to help each side do its job better within the context of your structure.

Scoliosis, Aging, and Internal Space

As many readers noted in their responses, scoliosis doesn’t stop at the musculoskeletal system.

Changes in ribcage and pelvic shape can influence the space available for internal organs over time. Thoracic curves may affect breathing capacity or cardiovascular endurance. Lumbar curves can influence digestive comfort or pelvic floor function. With age, these effects can become more noticeable—particularly if posture collapses or curves progress.

This is where elongation and expansion take on deeper meaning.

Creating space through posture, movement, and scoliosis-specific breathing supports not only spinal alignment, but organ function as well. When you lengthen your spine, you’re not just improving how you look or reducing pain—you’re creating room for your body to function optimally.

Breathing becomes circulation. Posture becomes digestion. Alignment becomes vitality.

A Whole-Body Perspective on Long-Term Health

Scoliosis care benefits from a whole-body perspective, especially as we age.

Proactive monitoring matters. Sharing your scoliosis history with healthcare providers helps ensure that symptoms are understood in structural context. A thoracic curve might explain why you feel short of breath during exercise. A lumbar curve might contribute to digestive issues that seem unrelated to your spine.

When movement respects the complexity of scoliosis—when it’s three-dimensional, specific, and informed—it supports not only posture, but longevity.

The Shift From Correction to Understanding

Scoliosis is not simply something to correct.

It is something to understand.

And understanding creates the opportunity for movement with intention, resilience, and ease—not just today, but decades from now.

The curve is part of your structure. The question isn’t whether you can make it disappear, but whether you can help your body adapt more efficiently, move more freely, and age more gracefully within that structure.

That’s the work. And it starts with seeing scoliosis for what it truly is: a syndrome, not just a shape.

What questions are emerging for you as you think about scoliosis long-term? Share in the comments below.